The Legislature in Intra-Executive Crisis and Institutional Instability in Nigeria- Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers- Open Access Journal of Annals of Reviews & Research

The Legislature in Intra-Executive Crisis and Institutional Instability in Nigeria- Juniper Publishers

Abstract

The preeminence of legitimate institutional preferences distinguishes popular government from dictatorship. The imperative for viable legislative institutions to the consolidation of popular government in Nigeria cannot be overemphasized. This study interrogates legislatures’ complicity in intra-executive conflicts, deputy-governorship turnover, and institutional instability, with a view to mitigate further undermining of the institution of the legislature. Qualitative method, descriptive analysis, theories of separation of powers, institutionalization, and the prebendal conception of the Nigeria state, its post-colonial and post-conflict transactional politics suffice. The 1999 Constitution features bicameral national, and unicameral subnational assemblies and multi-level executives. It enjoins separation of powers with delineation of the functional boundaries of governmental institutions vis-à-vis the rule of law to guard against encroachment and impunity. Sections 176 and 186 provide for Governor, and Deputy-Governor, common to all the thirty-six States. Sections 130 and 141 provide for President and Vice-President respectively. Deputy-Governor is significant, as next to, and prospective Governor. Governorship candidates pick running mate for election and voters express support for the duo correspondingly. However, the ‘potential advantage is often counteracted by the prevalence of crisis-ridden executives’, exacerbate by compromised legislatures. Subnational legislative-executive relationship was characterized by the manipulation of legislatures by Governors to personal political ends. Cases abound of intra-executive crisis of confidence that thwarted collective executive successes while leaving both institutions deeply divided amidst accusations, counter-accusations and indictments. A survey of these cases reveals extensive legislatures’ complicity in summary impeachment, forced resignation and intimidation of many Deputy-Governors on sundry allegations leading to high Deputy-Governorship turnover. Pliable legislatures became executives’ whipping tools at the disposal of Governors to whip uncooperative and recalcitrant deputies into line, within days in blatant subversion of the Constitution. Judicial reviews invalidating identified undue legislative interferences underscore vexed question on legislatures’ autonomy, internal complexity and universalism, making mockery of constitutional government.

Keywords: Nigeria; Institution; Legislature; Deputy-Governor and Turnover

Introduction

The preponderance of institutions in politics and government is what distinguishes developed from other democracies and other forms of government. While viable institutions are crucial to representative government, the preeminence of virile legislative institution in popular government cannot be over emphasized. The granted powers and actual disposition of the legislature in relations to other arms of government are crucial where and when separation of powers and the rule of law are of the essence. This paper further discussion on the Nigerian experience in subnational legislative-executive relation within the context of the shared characteristics of post-colonial and post-conflict systems of its kind including the transactional politics, pervasive defective state system, poverty and inequality, desperate quest for power, appropriation of the state and the reign of impunity. Incidences of intra-executive crisis between 1999 and 2015 raise questions on the legislature’s complicity in institutional instability. Nigeria is a federal entity with a national government and thirty-six constituent units otherwise refer to as States. The 1999 Constitution features corresponding multi-level executives, a bicameral national, and 36 unicameral state assemblies. The Constitution enjoins separation of powers and checks and balances that transcends branches of government to delineation of the functional boundaries of governmental institutions as well as the rule of law to guard against encroachment and impunity. It enjoins institutional autonomy in specific spheres and systemic mutual inter-dependence of the branches of government [1].

The Place of Governor and the Deputy-Governor

The Nigeria’s federal structure was bolstered with a constitutional guarantee of executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government at the subnational level [2]. State executive is the core of government often comprising elected and appointed officials with policymaking power. It includes the governor, deputy-governor, commissioners, and select career civil servants [3]. Thus, common to the 36 states of the federation is the institution of the governor and the deputy governor. Section 176 subsections (1) and (2) provides that, “There shall be for each State of the Federation a Governor. (2) The governor shall be the Chief Executive of that state. Governors wield enormous power in Nigeria and they deploy such power sometimes to the detriment of their deputies. The governor like the president has extensive discretionary executive powers including ‘limited authority’ over the state’s security forces domiciled in his/her state of authority. However, the scope of the executive powers and authority is limited by both the constitution as well as the realities of power and party politics [3]. For example, the 1999 Constitution requires that in exercising their powers, headship of state security institutions should seek final clearance from and are answerable to their superior federal authorities like the Inspector-General of Police, the Director-General of the State Security Service, the Chief of Army Staff and so on.

These are some of the constitutional restraints on state executive powers .Section 186 states that, “There shall be for each State of the Federation a Deputy Governor”, which has few constitutional duties and the primary significance of which is not in what it is but in what it might become, as second in command to the governor and prospective governor in the event of unforeseen circumstances. Section 188, subsections 1-11 outlines the procedure for the removal of governor from office, which is applicable to the Deputy-Governor as well. Subsection 11 entails “gross misconduct”, which it defines as a grave violation or breach of the provision of the constitution or a misconduct of such nature as amounts in the opinion of a state assembly to gross misconduct. Such erring executive official could be impeached by the legislature exclusively for acts and omissions amounting to gross misconduct. The legislature enjoys broad attitude in the exercise of discretion without clearly defined grounds for impeachment in the constitution, putting the executive at the mercy of the legislature. Section 145 outlines provisions for acting Governor during temporary absence of the Governor. Section 146, subsection 1 contains provisions on discharge of functions of Governor and it provides that the Deputy-Governor shall hold the office of Governor if the office of Governor becomes vacant by reason of death or resignation, impeachment, permanent incapacitation or the removal of the Governor from office for any reason in accordance with section 143 or 144 of the constitution.

Section 181(1) states that: “If a person duly elected as Governor dies before taking and subscribing to the Oath of Allegiance and oath of office, or is unable for any reason whatsoever to be sworn in, the person elected with him as Deputy governor shall be sworn in as Governor and he shall nominate a new Deputy-Governor who shall be appointed by the Governor with the approval of a simple majority of the House of Assembly of the State.” Section 191(1) also states that, the Deputy Governor of a State shall hold the office of Governor of the State if the office of Governor becomes vacant by reason of death, resignation, impeachment, permanent incapacity or removal of the governor from office for any other reason in accordance with section 188 or 189 of this constitution.” Governorship candidates select their own running mate for election and voters express support for a deputy-governorship candidate in the same way as they choose between the candidates for the governor [3].

On a joint ticket, the electorate votes for the governor and deputy-governor both of who should equally be accessible to the electorate on whose mandate the executive presides and whose legitimacy it governs and represents the state government. Section 187(1) states that, “In any election to which the foregoing provisions of this part of this Chapter relate a candidate for the office of Governor of a State shall not be deemed to have been validly nominated for such office unless he nominates another candidate as his associate for his running for the office of Governor, who is to occupy the office of Deputy Governor; and that candidate shall be deemed to have been duly elected to the office of Deputy Governor if the candidate who nominated him is duly elected as Governor in accordance with the said provisions.” Subsection (2) states that, “The provisions of this part of this Chapter relating to qualification for election, tenure of office, disqualifications, declaration of assets and liabilities and Oath of Governor shall apply in relation to the office of Deputy Governor as if references to Governor were references to Deputy Governor.” The composition and functioning of the state cabinet are at the discretion of the governor and cabinet meetings are often at the pleasure of the governors. Section 192, authorizes the governor to appoint commissioners and Section 193, empowers the governor to exercise his/her discretion in assigning executive responsibilities to commissioners so appointed or deputygovernor.

The potential advantage of dual executive can be and is often counteracted by the occurrence of ‘divided governments. While the constitution vested a Governor with wide-ranging powers like the president, the exercise of such powers, much more than what the constitution envisages, have occasionally been counterproductive. Governors often deploy such powers at will, demanding subservience to authority from elected and appointed political office holders including their deputies. Widespread impunity amidst arbitrary deployment of executive powers negates the spirit of the constitution and undermines trust, cooperation and unity of purpose crucial to the development of viable institution. [3] Observation suffice, to the extent that governors often grow too big for their boots acting in manner, often inconsistent with constitutional provisions. Desperate or ambitious governors seek collaboration of legislative assemblies that laid the ground for systemic collapse [4]. Cases abound of intra-institutional crisis of confidence and lack of cohesion within state executives that thwarted collective executive successes, as this paper shall highlight.

Theoretical and Contextual Framework

State executives’ manipulation of their respective assemblies to limited ends and the attendant institutional instability cannot be divorced from the desperate quest for power among political actors who will commit anything and everything to capture and retain power. This is not necessarily for common good but rather for selfish ends to which state powers and resources can as well be committed [5]. Equally important is the authoritarian disposition of the ruling elite, which was inherited from the military rule. This disposition tinted their understanding of politics as a do or die affairs and the politics of power depicting the survival of the fittest. The politics lacks ideology but rather embrace the deployment of both legal and extra-legal means to seek, use and retain their hold on power and access to state resources [5,6]. As noted elsewhere, the military ethics of command structure, loyalty, and obedience penetrated politics thereby outlawing dissent and opposition within and without. Governmental institutions are mere instruments at the disposal of the political and the ruling elites to feather their nest and manipulate at will to advance personal causes.

Political party formation and party politics are also rooted in these dynamics, much the same, in the dynamics of the Nigerian society. The understanding of this interplay of forces ‘holds useful insights into the behavior of political actors and provides reasonable expectations concerning their actions.’ There is heavy premium on political power such that political actors take the most extreme measures in the political contestation. This is more so that he who has power by all estimation owns everything [5]. Ake’s submission captures the successive rivalries and desperation often characteristic of party politics. Political rivalries within the same political party gets more intense than between parties especially when one party is stronger, wieldy and command wider reach than other smaller politically less significant political parties with limited electoral value. Political partners within the party soon become sworn enemies. Political alliances crumble and consideration of party switching takes precedence over principled bargaining, compromise and mass appeal at the slightest provocation, largely for reasons of personal political ambition. The ensuing battle for supremacy essentially often resorts to the repeated intense intra and interinstitutional competitions, which has grounded governance and administration in many states. The uncompromising disposition of major actors manifested in the politics of exclusion, mutual distrust, crisis of confidence and institutional instability.

The above is not excusing the legislative institutions from the challenges of institutionalization threatening their viability within the context of Plosby’s three main subject areas namely; autonomy, internal complexity and universalism [6]. An understanding of state assemblies’ interaction with their environment vis-à-vis their internal characteristics are of the essence in appreciating their malleability or predisposition to external influences. The manipulation of state assemblies to selfish ends by governors makes an appreciation of Joseph’s conception of the Nigeria state and politics and Polsby theory of institutionalization contextually relevant. This is more so that, the Nigeria’s thirty-six states thrived on economic inequality, lacked resources, and entrenched legacy of central dominance. They have shared history of limited governmental, party politics, systemic and institutional inadequacies, notwithstanding variation in socio-cultural configuration. Thus, in furtherance of discussion on representative government, separation of powers, rule of law, and the centrality of institutional viability to the consolidation of representative government, this paper explores legislature’s complicity in intra-institutional crisis and institutional instability during the period under review. The legislature’s complicity in the identified instances of in-fighting and crisis of confidence in states’ executive have had both destabilizing and conflictual elements [7].

Analysis and Discussion of Findings

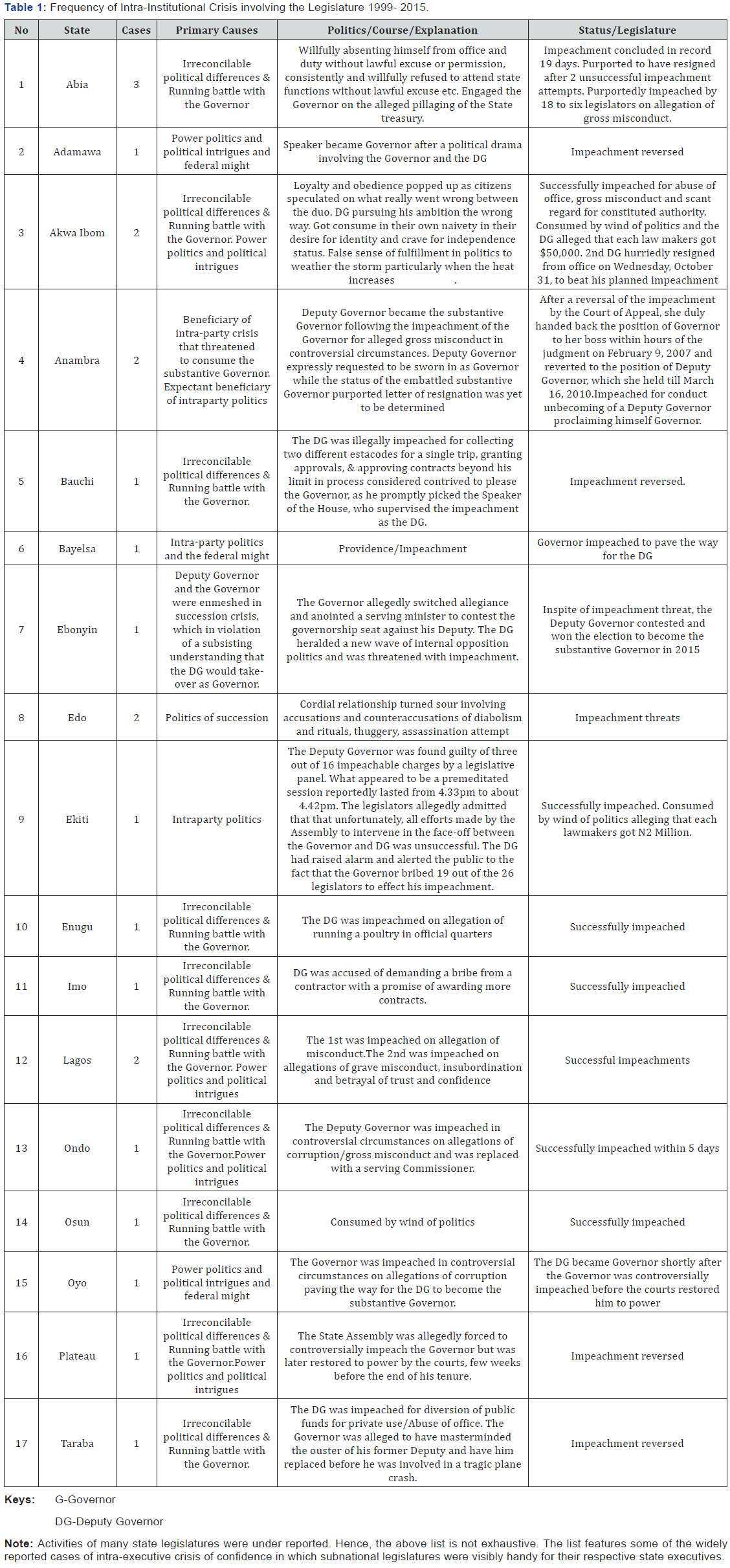

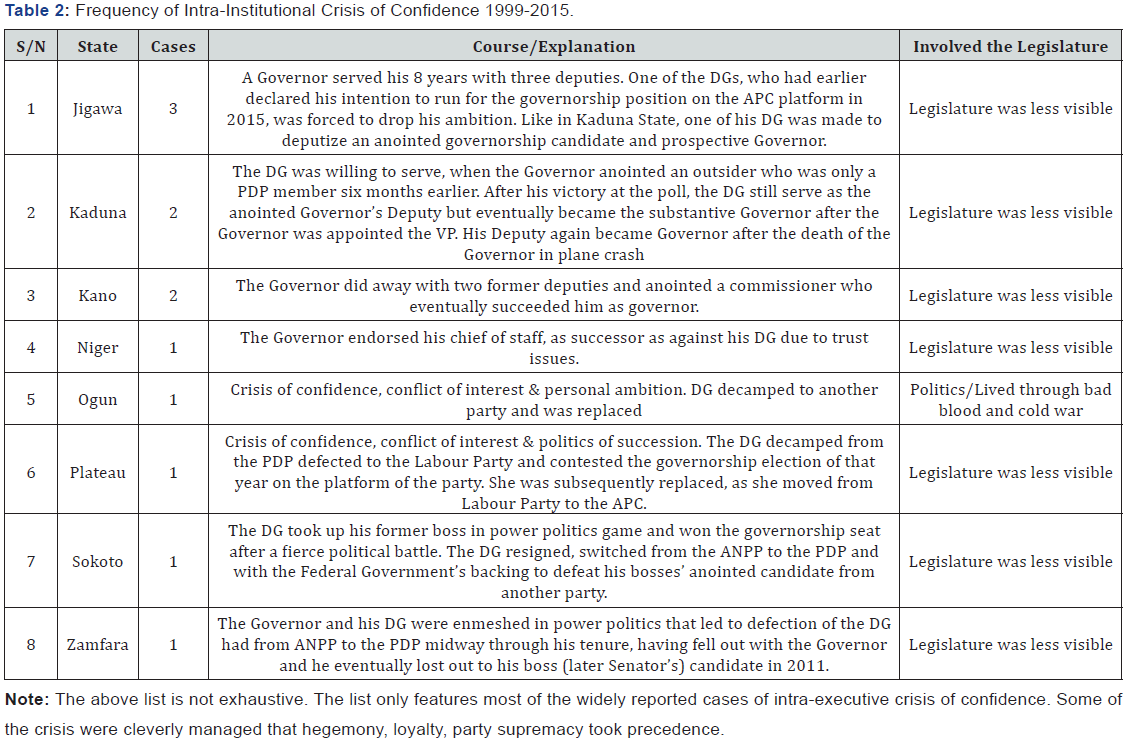

The pre-1999 personalized authoritarian leadership styles that undermined the viability of governmental institutions reigned supreme. State governors actively participated in producing and removing the leadership of their respective state assemblies. Beneficiaries of such benevolence in the legislature go extra mile to please their benefactors with flawed impeachment campaigns, as Table 1 shows. In transactional politics, pliable and reckless state assemblies launched impeachment campaigns in controversial circumstances. Deputy Governors were victims of party politics with the preeminence of personal preferences of strong personalities as opposed to institutional preferences, as Table 2 reveals. This accounted for high turnover of deputy governors, undermined separation of powers and the rule of law and halted governance in some of the affected States like Anambra, Adamawa, and Taraba. A survey of intra-executive crisis reveals extensive legislature’s complicity in impunity, arising from the arbitrary deployment of impeachment campaign, forced resignation and intimidation of many deputy governors on sundry allegations, as Tables 1 & 2 reveal.

State assemblies became whipping tools at the disposal of State Governors to whip uncooperative and recalcitrant Deputies into line. This manipulation of legislative institutions granted state governors asymmetric advantage over their deputies. Many of the partnerships started well and on cordial notes. Governors either enjoyed the benefit of picking their running mates or had them handed over by party stalwarts, stakeholders, interest groups or power blocs. They were usually experts and achievers in their own rights, professionally qualified, as their ‘colleague’ governors. Some with political clout, formidable intra-party structure, network of loyalists across parties, interests and platforms and strong personalities, as the governors. Some were not as ambitious, or such were overshadowed by their levelheaded, gentleman posture, loyal and obedient disposition. This paper is not to embark on a wholesale story or inventory of crisis but to run an overview of intra institutional crisis as it involved the legislature during the period under review (Table 1,2).

Executives in a State of Flux

The relationship between governors and their deputies could be classified as one of trust, mutual distrust, suspicion, of loyalty, resentment, welcome and despise and of obeisance and the pursuit of personal ambition. Survey reveals that problem often arisen from crisis of succession, as Governors often become weary of having their deputies succeed them. A Deputy Governor should naturally be an individual with the best chance to succeed an outgoing Governor, going by the fact that he/she is constitutionally mandated to take-over in the event of any unforeseen circumstance like death, impeachment or incapacitation. A Deputy is seen as the closest working ally of his principal and that underscores the exclusive constitutional right granted prospective Governors to determine their running mates. However, this was not the case between 1999-2015, as their respective Governors visibly resented many Deputy Governors. O bserved that only one Deputy Governor, Zamfara State was able to succeed his principal with the consent of that principal between 1999 and prior to the 2015 general elections [8].

In Abia State, the face-off between the Governor and Deputy- Governor 1999-2003, which culminated in the purported impeachment of Abaribe as Deputy Governor in 2000 divided the state chapter of ruling party, PDP amidst accusations and counter-accusations. This is not withstanding the fact that the Governor nominated the Deputy-Governor who became the State’s Deputy Governor after a successful gubernatorial election in 1999. The State Assembly launched impeachment campaign against the Deputy Governor twice in 2000 and a third time in 2003. The embattled DG resigned early in 2003, as he was facing his third impeachment, sending his resignation letter by courier for the record. The House of Assembly formally voted him out of office several days later, in a move Abaribe likened to “medicine after death”. The ousted DG contested the gubernatorial election on the platform of the All Nigeria Peoples Party (ANPP) in 2003, but lost to his principal, Orji Uzor Kalu of the ruling PDP. Abaribe’s faceoff with Kalu within three months of their electoral victory to the effrontery the former exhibited in challenging the latter’s purported pillage of the state’s treasury. The DG had reportedly accused his principal of personalizing government business and shortchanging the populace [9]. Similarly, the erst while Deputy Governor of Osun State, Iyiola Omisore, was impeached in 2002 notwithstanding that he was the popular choice as Deputy Governor to his principal, Bisi Akande at the time (Table 1 number 14).

[8] Reported further that only a handful of Deputy Governors were able to succeed their Governors whose seats were made vacant by divine occurrences like death, as the case with Taraba and Kaduna States and by controversial circumstances like impeachments or through one form of political crises or the other. For example Goodluck Jonathan succeeded Diepreye Alamasiegha as Governor of Bayelsa State after the Bayelsa State House of Assembly impeached the latter on the grounds of corruption and money laundering (Table 1 number 6). Mukhtar Ramalan Yero of Kaduna State and Ibrahim Geidam of Yobe State, hitherto Deputy Governors, became Governors after the deaths of Sir Patrick Yakowa in a plane crash and Senator Mamman Ali due to ill-health respectively. Adebayo Alao Akala of Oyo State became Governor for a brief period after Governor Rashidi Ladoja was controversially impeached before the courts restored him to power (Table 1 number 15). Late Michael Botmang of Plateau State became Governor briefly after the State Assembly members were allegedly forced to controversially impeach Joshua Dariye who was later reinstated by the courts, few weeks before the end of his tenure (Table 1 number 14). Governor Peter Obi of Anambra State was impeached in similar circumstances for his deputy, Virginia Etiaba to become Governor briefly before the courts reinstated Obi. Former Adamawa State Deputy Governor, Bala James Ngilari became Governor after a political drama involving him, his principal and the State House of Assembly unfolded (Table 1 number 2).

According to 18. Alvarez account, political crisis also brought some Deputy Governors to power. For example, Aliyu Wammako of Sokoto State became Governor after a fierce political battle with his former boss, Governor Attahiru Dalhatu Bafarawa (Table 2 number 7). Wammako resigned, left the All Nigeria’s Peoples Party (ANPP) to the ruling PDP and with the Federal Government’s support, he defeated Bafarawa’s candidate who contested under Democratic People’s Party (DPP). Perhaps, the identified Deputy Governors would not have become Governors without the circumstances that brought them to power, as there was no clear indication that their respective governors in their quests would have supported them to clinch the posts. For example, as findings reveal (Table 1 number 17), it was not of the wish of Governor Danbaba Suntai’s loyalists that the Deputy Governor and acting Governor, Garba Umar (who acted for months while Suntai was bedridden assume the governorship of Taraba State. Suntai was alleged to have colluded with the state assembly to mastermind the controversial ouster of his former Deputy and have him replaced with an Acting Governor some few weeks before he was involved in a plane crash. The former Deputy Governor challenged his removal and had his purported impeachment quashed [10].

Governors and their deputies lived with bad blood and misunderstanding between them, in some cases for reason that deputies expressed interest in governorship seats. Virtually all deputy governors nursed the ambition of succeeding their governors (Table 2 numbers 1 - 8). Many were summarily dealt with through intimidation and outright express removal from office. Amir recalled an instance when a particular Deputy Governor, having known so well that his Governor will not support his gubernatorial ambition if he decides to succeed him, settled for a senatorial ticket under the PDP. Incidentally, his principal was also nursing a senatorial ambition for a different constituency. The Governor worked against his Deputy’s senatorial ambition on the ground that he cannot sit on equal terms in the same chamber with his former Deputy. Understandably, some Governors (Table 1 numbers 3, 8, 13) forced their Deputies out of office through politically motivated impeachment campaigns or consistent persecutions and denial of responsibilities. The ousted Deputy Governor of Akwa Ibom State, Nsima Ekere hurriedly resigned from office to beat his planned impeachment by the State Assembly [11]. Series of allegation such as running poultry in Government House and insubordination were also advanced to impeach some Deputy Governors, as witnessed in Imo and Enugu States (Table 1 number 11). Again, in Plateau State, in pursuit of her gubernatorial ambition, Pauline Tallen, who was Governor Jonah Jang’s Deputy up to 2011, defected to the Labour Party and contested the governorship election of that year on the platform of the party (Table 2 number 6).

Many of the partnerships started on a good note and but never end well. Some Deputy Governors were adopted as ‘political son’ for governorship election even though they never had any strong bond other than strained relationship with their governors thereafter. Once the governors get to know of their ambitions, they become weary and suspicious that the deputies were either plotting to oust or undermine them. Speakers and legislators who were strong political allies of, and sympathetic to the governors causes confronted their deputies with allegations of insubordination and betrayal [12]. For example, [13] noted that though, watchers of events in Akwa Ibom state likened the deteriorated relationship between Attah and his erstwhile deputy to pure politics and power intrigues, as for the State Assembly, which effected the latter’s impeachment, the exercise was predicated on abuse of office, gross misconduct and scant regard for constituted authority. The intrigues that culminated in deputy governors’ impeachment and the controversy that trailed the exercise attest to vendetta, power play and crisis of succession.

In Jigawa State (Table 2 number 1), former Governor Ibrahim Saminu Turaki served his 8 years with three deputies and in Bauchi (Table 1 number 5), Governor Yuguda had to part with his once formidable Deputy, Garba Gadi in controversial circumstances. There was no love lust between former Governor Ibrahim Shekarau of Kano State and the two Deputy Governors that served him, as both tried frantically to succeed him in 2003 and 2007. The refusal of some Deputy Governors to defect with their Governors and the counter defections of some Deputy Governors to different political parties from their principal also indicated a sign of silent internal conflicts between Governors and their Deputies (Table 1 number 13, and Table 2 number 5, 7 & 8). In [14] account, the State legislature was reportedly deployed by Governor Mimiko of Ondo State to get at his Deputy, Ali Olanusi for defecting from the ruling Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) to the opposition All Progressives Congress (APC). The irreconcilable political differences between the two principal officers culminated in the State Assembly initiating an impeachment campaign against the Deputy Governor. The latter was subsequently removed from office in controversial circumstances on allegations of corruption and gross misconduct. He was expressly replaced by Commissioner for Agriculture, Lasisi Oluboyo. In a process that lasted barely a week from the service of the impeachment notice on the Deputy Governor, 22 members of the House in a voice vote expressed their support for or objection to the removal of the Deputy Governor. Olanusi consequently directed to hand over all government property in his possession to the permanent secretary in the deputy governor’s office who was also mandated to use every lawful means to retrieve all the property should Olanusi fail to release them forthwith [14].

There is no gainsaying the fact that some Deputy Governors accepted to serve in the hope that they would be supported to succeed their principals after the completion of their terms of office. Conversely, virtually all former Deputy Governors from 1999 to 2015 had such political ambition abruptly terminated, simply because their Governors felt uncomfortable and therefore, uncooperative. Whereas a number of Governors readily advanced allegation of disloyalty against their Deputies, cases abound where visibly loyal and obedient Deputies for 8 or more years, suffered rejection at the slightest provocation (Table 1 numbers 5, 8, and 13). These Deputies were shortchanged and substituted with other presumably loyal and trustworthy protégés of the Governors. The Governors pitched tents with such principal officers like their Chief of Staff, Secretary to the State Government (SSGs), commissioners or even party stalwarts outside their cabinets. Some of these individuals were even propped up unprepared for governorship. In other cases, Governors will support individuals outside government establishments.

For example, in Kaduna State, Ahmed Makarfi bypassed his Deputy, late Patrick Yakowa and instead anointed Namadi Sambo, who had not even been a PDP member six months earlier. Yakowa was asked to serve as Sambo’s Deputy. In Kano State, Ibrahim Shekarau anointed his commissioner and personal friend as against his deputy, Abdullahi Gwarzo to succeed him. In Kwara State, one of Bukola Saraki’s Commissioners, Abdulfatah Ahmed was favoured instead of Saraki’s Deputy; Governor Kashim Shettima of Borno was Ali Modu Sheriff’s Commissioner; Godswill Akpabio of Akwa-Ibom State was Obong Victor Attah’s former Commissioner; Governor Gabriel Suswam of Benue, who was a House of Representatives Member was preferred by George Akume to his Deputy; Governor Liyel Imoke of Cross Rivers, a former senator was preferred by Donald Duke to his Deputy. This was inspite of the fact that most deputies possess the relevant qualifications and pre-requisite experience to continue from where the bosses stopped.

The independent mindedness of some deputies was misconstrued to mean effrontery by their principals. Thus, irreconcilable political differences brewed especially where the DG was a political asset with strong base and robust followership. Such personalities were difficult to tame or whip into line. In such instances, lawmakers participated in major breach of fair hearing as provided under Section 36 of the 1999 Constitution, perpetrating illegalities by conniving with Governors to summarily remove their Deputies in premeditated processes. These illegalities, often pursued in haste deliberately ignored subsection 6 of Section 188 of the I999 Constitution which states that, “the holder of an office whose conduct is being investigated under this section shall have the right to defend himself in person or be represented before the panel by a legal practitioner of his own choice.” As noted earlier, such disregard for the rule of law explains why the Bauchi State Governor denied Garba Gadi due privileges inspite of court pronouncement in his favour as the authentic Deputy Governor. Governor Yuguda instead created an alternative office from where someone else held sway as Deputy Governor when the State House of Assembly impeached his Deputy illegally.

[15] Reasoned and rightly too that the Deputy Governors fate were not unconnected with a seeming gap in the Constitution. The 1999 constitution does not assign any specific role to the Deputy Governor, thereby leaving this office at the mercy of delegation of duties at the discretion of the Governor. The effectiveness or active role of the deputy therefore lies almost entirely on the willingness of the governor in creating the right platform. Section 193 (1) of the 1999 constitution granted the governor power to assign responsibilities of the government to the deputy governor including the administration of any department .The position of the First Lady enjoyed prominence than Deputy Governorship, which Nigerians viewed and sarcastically referred to as ‘spare tyre’ [16]. Among other issues, the manner of emergence of Deputy Governors cannot be divorced from this problem. For example, [16] recalled that Jigawa State Deputy Governor, Ibrahim Hassan Hadejia, who had earlier declared his intention to run for the governorship position on the APC platform in the 2015 general elections, was forced to drop his ambition when the party caucus decided to produce a candidate by consensus. The end product was Governor Mohammad Badaru Abubakar and Hadejia who was former deputy to Turaki was made to again, deputize Badaru. In the ensuing scenarios, the line between dictatorship and popular government was blurred with a compromised legislature that gave room for personal rule to thrive.

By and large, in emerging democracies like Nigeria, legislature must take the lead in defining operational boundaries. As noted elsewhere [17], the speed with which impeachment proceedings against Deputy Governors were conducted for reasons of distrust, absolute loss of confidence and betrayal, controversies that trailed such exercises, judicial pronouncements to the contrary, post-exercise self-confession of legislators, denial of opportunity for self-defend, post-impeachment politics of who succeed the impeached deputies usually between Speakers and other interests among others were indication that the legislature undermined institutional instability during the period under review [18,19]. The legislature is too important and too crucial to popular government for its operation to be left at the discretion of a single executive, aided by transactional politics. The Governor’s position of advantage in the distribution of projects, control of state resources, and on whose table the buck stops was to the disadvantage of the Deputy Governor with no clear-cut constitutional responsibilities except as delegated by the Governor.

Concluding remarks

This paper acknowledges the nature and character of the

state system, distorted development trajectory of representative

institutions and the peculiar circumstances of successive

electoral processes as some of the consequences of the chaotic

party politics that hinder legislative performance and undermine

representative government. The foregoing underscores the

centrality of the legislature in the political and power relation

dynamic not only as game changer but also as the carrier of hope

on whom the popular will is entrusted and as the custodian of the

mass mandate. This implies that the legislature must neither be

the promoter of personal interest nor champion of personal ego

by turning itself to an appendage of the executive in whatever

guise. It must not be tool of vendetta to settle political scores

either. Subnational legislatures are significant governmental

institutions with far-reaching impact. The Nigeria’s component

units constitute significant testing grounds for national politics

and national leadership [20,21]. National politics, federal policy

and programmed are also felt directly at the subnational level

and what goes on at the state level determine national politics.

The summary impeachment, and threat of impeachment against

many Deputy Governors smacked of disregard for the rule of

law turning the legislature to “executive’s whipping tool” at the

disposal of the Governors. The continued legislature’s meddling

in executive affairs compromises separation of powers, and

legislature’s independence and undermines the rule of law. It shortchanges the electorate and negates the spirit of popular

government. It entrenches the loss of sense of belonging on part

of the victim Deputy-Governors’ constituencies. By yielding to

the antics of the chief executive, as a clearing house, it tends to

legitimize executive’s illegal conducts including subversion of

the constitution through tenure elongation, misappropriation of

funds and rubber stamping of executive bills. Inter-institutional

relation must be observed responsibly and in conformity with

the Constitution. The citizenry should be more active in calling

legislators to account at the state level to enhance the quality of

representation.

To know more about Juniper Publishers please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/aboutus.php

For more articles in Open

Access Journal of Reviews & Research please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/arr/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment